Governance of natural resources

-

- Are there existing constitutional and other legal provisions to respect, guarantee and enforce the right to land, water and other natural resources, in particular, for peasants, Indigenous Peoples, small-scale fishers, pastoralists, and other ethnic and marginalized groups?

- Are existing measures to respect, protect, guarantee and promote legitimate tenure rights effectively implemented in a non-discriminatory way? Do they give priority to the above-mentioned groups and other marginalized groups?

- Do existing national extractive policies (especially around the governance of sub-soil resources) impede communities’ access to and control over their lands, forests, fisheries, water resources, biodiversity and other natural resources?

-

For example, when a mining company pollutes community water resources, destroys aquatic organisms, dumps wastes on forests and grazing lands or on farmland leading to loss of crops?

-

- Which measures are in place to recognize and protect collective and/or customary tenure rights and systems?

- Which measures are in place to guarantee legitimate rights over publicly owned lands, fisheries and forests, including those used and managed collectively (‘the commons‘)? How are issues such as adequate compensation, resettlement and restitution safeguarded in constitutional and legal provisions? Is the notion of ‘public purpose or public interest’ defined in law?

- Are there accessible, transparent, participatory and gender-sensitive programs and mechanisms to effectively monitor the outcome of land and associated natural resource governance in order to achieve food sovereignty, poverty eradication, sustainable rural development, and social stability, among others?

-

What measures are in place to avoid infringement of legitimate tenure rights that are not currently protected by law, of women, peasants, Indigenous Peoples, small-scale fishers, pastoralists, ethnic groups, and other marginalized groups?

-

For example, are legal provisions in place to rule out forced evictions?

-

- Are there contradictions between laws and frameworks regulating natural resource management, tenure, agriculture, fisheries and frameworks regulating other sectors such as extractive activities, mining, trade, environmental protection and climate change among others? What mechanisms are in place to address existing contradictions to ensure policy coherence based on human rights?

-

Are there also measures in place to regulate, monitor and hold accountable non-state actors, such as corporations and/or financial investors who operate in the land sector?

-

Are there bills or laws, which limit access to and the use of water by rural or urban communities, especially for food producers in villages or in other ethnic communities?

-

Are there also measures taken to protect vulnerable persons (e.g. orphans/child-headed households) against the loss of their tenure rights and access to natural resources?

-

What mechanisms are in place to ensure that women, peasants, small-scale fishers, Indigenous Peoples, pastoralists, ethnic groups and other marginalized groups have effective access to justice?

-

- What measures are in place to ensure that processes to identify, demarcate and record tenure rights are non-discriminatory (including through digital technologies), transparent and ensure effective participation by all rights holders, in particular marginalized people, taking into account existing power imbalances between different actors? Are tenure rights recorded in a way that ensure accessibility and socio-cultural appropriateness (including in the context of digital registries)?[61]

- Are nomadic pastoralists and forest dwellers entitled to use traditional (transhumance) routes? Are such provisions effectively implemented?

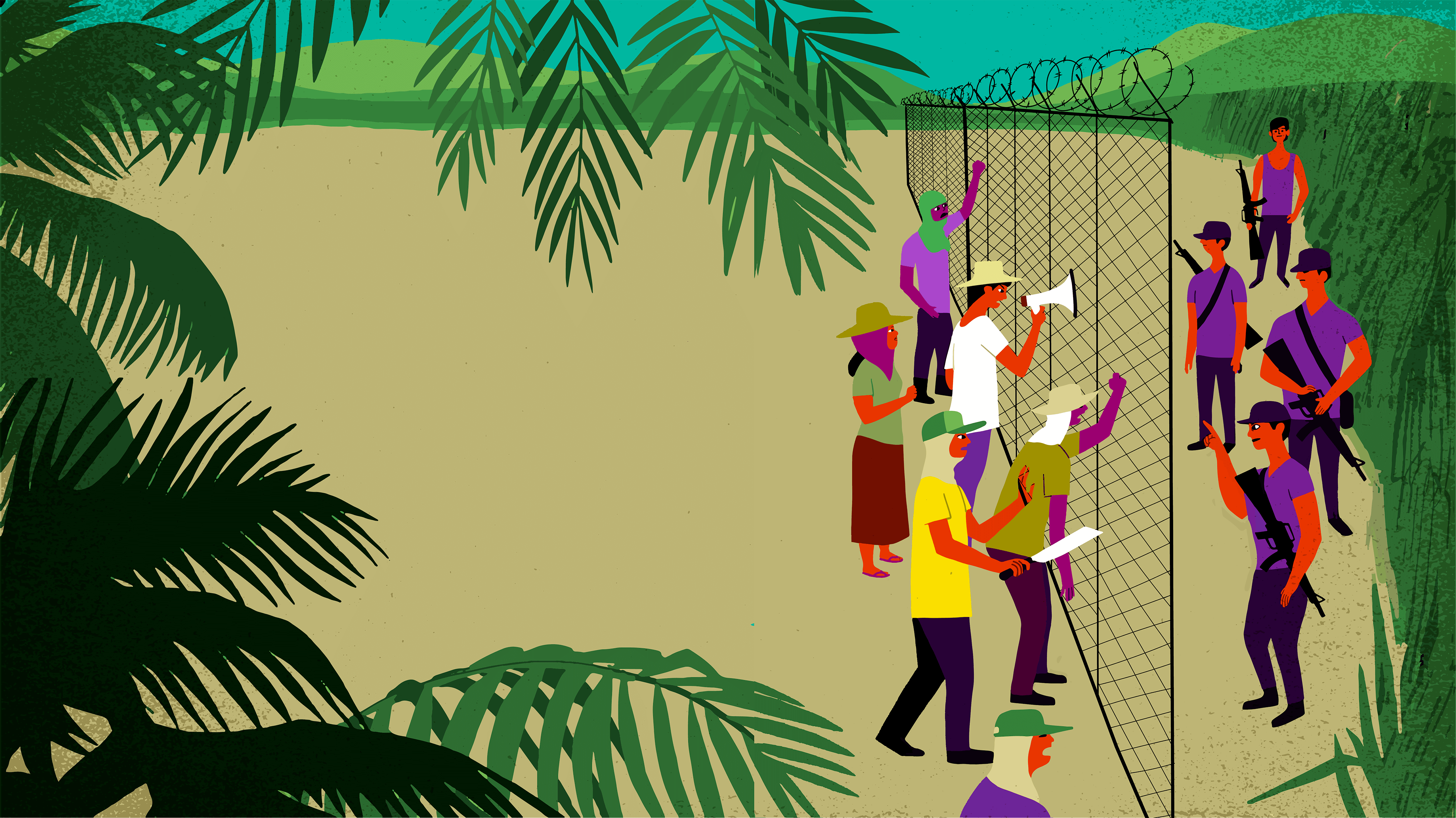

- Can small-scale food producers, including peasants, indigenous peoples, pastoralists, small-scale fishers and fish workers, agricultural workers and ethnic groups freely organize in associations to defend their rights over natural resources?

- What mechanisms exist to ensure the effective participation of social organizations in policy processes, in particular the organizations of peasants, Indigenous Peoples, pastoralists, small-scale fishers (and fish workers), agricultural workers and ethnic groups? Do these take into account existing power imbalances between different actors?